Story of the week

Get Backyard History's Newest Article in Your Inbox Every Week — For Free!

Articles

The Backyard History Store

Backyard HIstory

Backyard History is a popular newspaper column, podcast, and books written by Andrew MacLean, telling forgotten stories of Atlantic Canada's past.

Backyard History unearths the often hilarious, mostly mysterious, always surprising untold tales of Canada’s East Coast, as only a Maritimer can spin them.

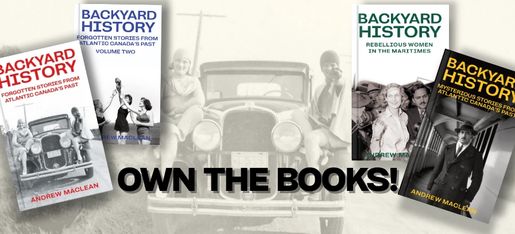

The best of Backyard History is in the books!

And the books are exclusively available right here at backyardhistory.ca!

.png/:/cr=t:0%25,l:0%25,w:100%25,h:100%25/rs=h:500,cg:true)